Menu

The significance of the girth for a horse's performance is considerable. We know that certain types of equipment – from bits to saddles and underpads – exert different types of pressure on the horse. But what about the gear that from a young age we learn to fasten as tightly as possible? How does the pressure of the girth affect the horse and its performance ability? Actually, a lot more than we think.

The primary function of the girth is to keep the saddle in place. If the girth doesn't lie optimally on the horse, it will affect the horse's performance, comfort, and the quality of its gait. Studies have shown that the girth often actually limits the range of motion and reduces the horse's ability to take in enough oxygen during riding if it's not positioned correctly. It has previously been assumed that the maximum pressure from the girth lies on the sternum. But the area that suffers most under the pressure of the girth is actually the point behind the elbow.

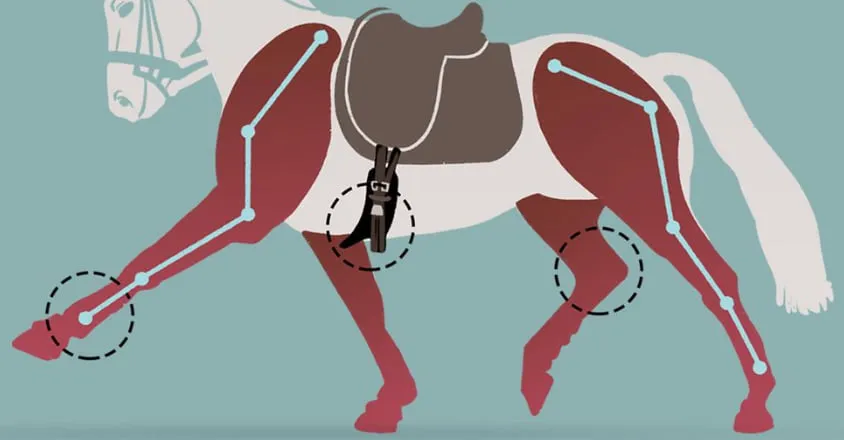

In a study conducted by Fairfax Saddlery.com, up to a 33% improvement in horses' movement patterns was recorded as soon as a correctly fitted girth was put on the horses (figure 1).

Looking at the horse's movement pattern in slow motion, it can be seen that the pressure from the girth consistently occurs in the same place, namely when the horse has one foreleg fully extended, and the other foreleg is vertical and in contact with the ground (figure 1).

Researchers have also examined when the girth presses the most on show jumpers. Here the maximum pressure from the girth was registered when the horse took off in front of the jump and the weight was shifted from the hind legs to the forelegs. When it landed over a jump of 1.4 meters, the pressure behind the elbow increased from 2.3 kg per square centimetre to 6.5 kg. per square centimetre with a standard girth.

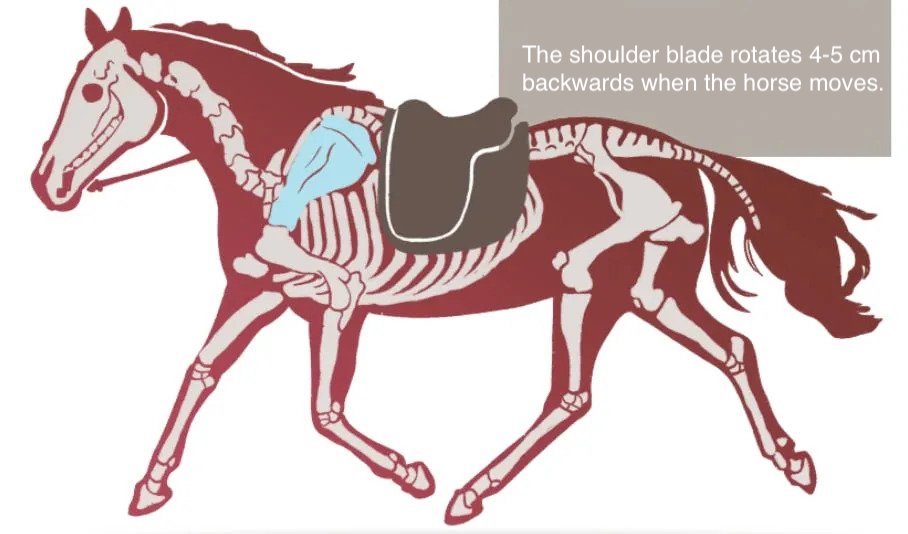

It is often seen that the saddle is positioned too far forward, disturbing the rotation of the shoulders. And often the culprit is the girth. If the horse's shoulder blade is naturally positioned further back than its girth groove, it can end badly. Saddles are equipped with girth straps that angle forward. Even if you put the saddle far enough back, it will quickly begin to slide forward to adjust to the angle of the girth straps if the girth is wrong. The result is that the saddle will lay on the shoulder blade and hinder the horse's movement pattern (figure 2).

The horse's shoulder blade makes a rotational movement when the horse is in motion. Therefore, you need to ensure that the saddle gives the horse about five cm of free space so that the shoulder blade can move. If you're in doubt, you can use your hand to measure.

Place the saddle on the back of the horse and let it slide into place. Find the edge of the shoulder blade with your fingers and see if you can fit at least three fingers. You can also get someone to lift the horse's foreleg and stretch it forward. Then you can see how much space behind the shoulder your horse really needs.

When you walk into a riding equipment shop, it's easy to be overwhelmed by the many types of girths available on the market. And on top of this, there are also many things you need to consider when choosing a girth. For example, the shape that should fit your horse's anatomy, the length, and not least the material.

Depending on the length of the girth straps, you need a girth with a short or long circumference. Short girths are designed for saddles with long straps and vice versa. Most dressage saddles are equipped with long straps, which is why you should choose a short girth, whereas jumping saddles are equipped with short girth straps, so you should use a long girth.

Many riders choose a girth that is too long for the horse. The tightening section should be higher than the horse's elbow to avoid bothering it when it moves. The ends of the girth should be close to the underpad, but without touching it. As a rule of thumb, you should be able to have at least three fingers from the underpad to the top of the girth.

Read also (sponsored content): A balm with a story…

Here follows an explanation of how the typical elements on a dressage girth should fit the horse (figure 3). For the girth to generally work optimally, it's important that the stretch from the elastic bands and the girth itself allows room for shoulders, elbows and, most importantly, that your horse can breathe. Therefore, you should be mindful not to tighten the girth more than the large D-ring (1) – if your girth has one – stays behind the strap and the middle seams do not break (2). Also, the buckles (3) must always stay behind the straps (4). If this is not possible, your girth is too long for your horse.

A clever way to find your horse's girth size is by placing the saddle on its back and fastening your old girth in the 2nd lowest hole on both sides. Then measure the girth with a tape measure from hole to hole and you have the length of the ideal girth for your horse.

No horses are, as we know, the same. The essence of choosing a girth for the horse is therefore that it should fit your particular horse's shape. Ergonomic girths are clearly the most dominant on the market. The key function of them is the shape, which provides maximum space for the horse's elbows and ensures shoulder freedom, which also prevents skin folds in and pressure in the girth groove and distributes the pressure on the sternum.

Asymmetrical girths (curved on one side and straight on the other) work well for horses that have a less defined girth groove that is closer to the elbows, which causes the girth to lie further forward than an ergonomic one.

Banana girths are designed for horses with short backs, wide ribs and a narrow chest, where the saddle tends to slide forward. These girths are designed to accommodate the rounder shape of the ribs and prevent the saddle from sliding forward and laying on the shoulders or rubbing against the elbows.

Far too many horses have girths that are too tight. If the straps are tightened too much, it actually takes away some of the space from the horse that it needs to move freely and breathe properly. Girths should always be tightened gradually and equally on both sides. A properly fitted girth has the widest piece between the legs in the middle and the narrow at the elbows. The buckles should sit at the same height on each side.

If the girth is tightened correctly, you will be able to slide your palm under it on each side without the horse reacting. It should feel like a polite handshake and not as if your hand is being squashed flat.

There are many different padding materials for girths. Besides the classic neoprene girth, they also come in leather, some are padded with gel, while others are made of memory foam. For both gel and memory foam, they are designed to adapt extremely well to the horse's body and reduce pressure points. This is especially important when using dressage girths. The rule of thumb is, if it feels comfortable for you, your horse is likely to agree.

Read also: Basic riding: Teach your horse to use its topline correctly